on

Services at the edge?

In a previous post, Silvano has discussed the basics of Clos topologies in data center networks, and has seen how they enable us to achieve extremely high aggregate bandwidth. For example, let’s use as a leaf a switch with 64 ports at 100 Gbps (ubiquitous these days) and connect 24 ports as uplinks. This configuration deploys 24 spine switches for a total aggregated bandwidth of 6.4 x 24 = 153 Tbps!

Now let’s consider how to implement in this example network security and visibility services, like firewall, micro-segmentation, load-balancing, tap network. The classical solution has been to use discrete appliances dedicated to a particular service and implement “service chaining” when more than one appliance must act on the traffic.

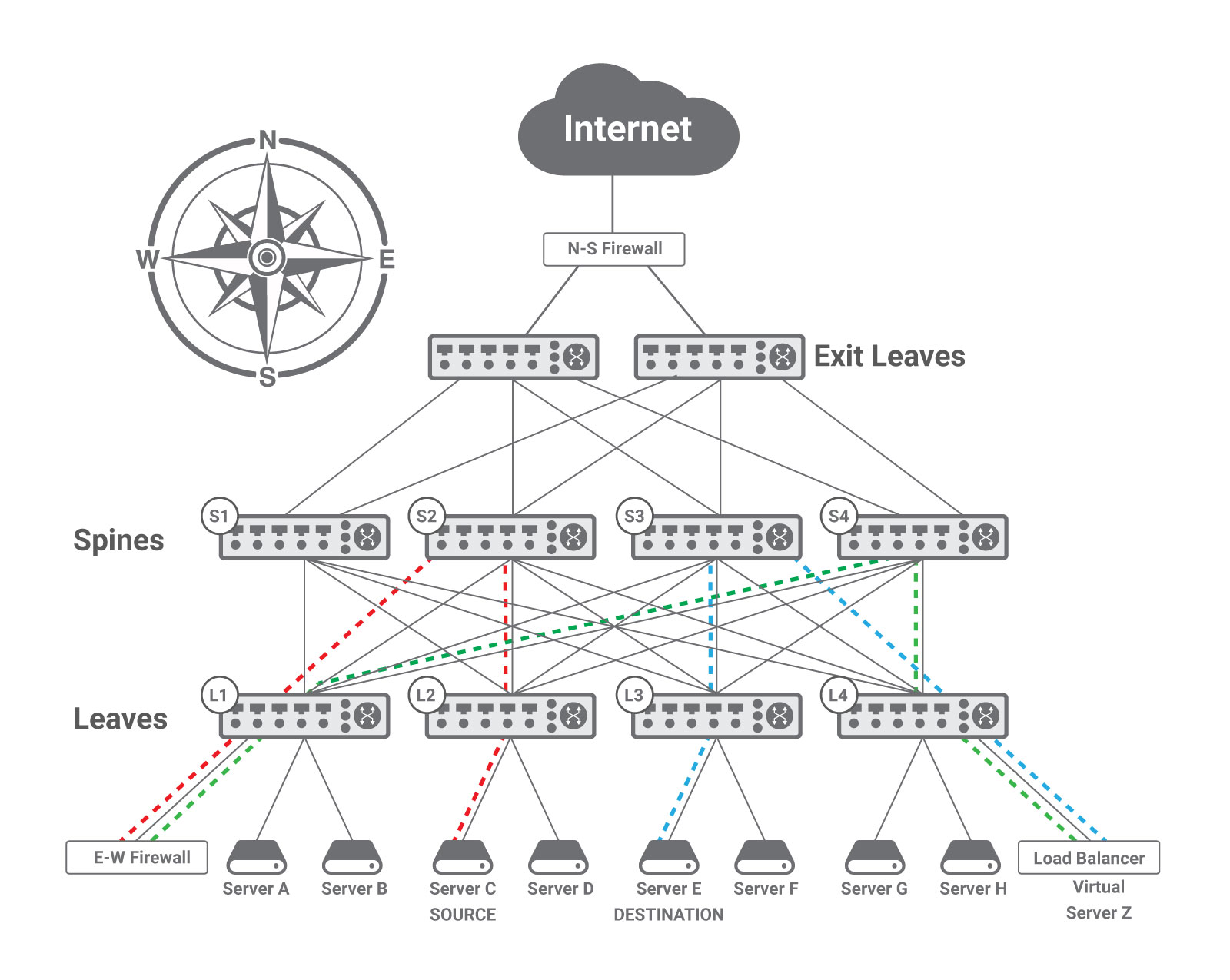

This works relatively well for the so called North-South traffic, i.e., the traffic going in and out the data center, such as Internet traffic. The figure below shows a typical way of interconnecting the data center network to the Internet, with a natural point of passage for all the North-South traffic where appliances can be located and traversed by traffic, as it is the case with the N-S Firewall. In addition, the bandwidth to the Internet is always significantly lower than the one inside the data center, hence it is reasonable to assume that appliances are capable of operating at line rate without choking the communications.

The East-West Challenges

The same does not apply to East-West traffic that is easily one order of magnitude larger than the North-South one, and appliances become a giant bottleneck or choke-point for the traffic. No appliance exists today in the market capable of supporting the 153 Tbps of our hypothetical (but quite realistic) network, not even for very basic services.

Moreover, East-West traffic uses many different paths through the Clos fabric, as explained in the previous post. Consequently, there is no spot through which all traffic is going where an appliance can be placed; rather traffic has to be purposely steered through the appliance. For example, let’s take the communication between two hosts that needs to go through a firewall and a load balancer. The figure above shows the case of a Server C communicating with Virtual Server Z, which is in reality a load balancer front ending Server E. For security reasons, the communication between Server C and Virtual Server Z must go through a firewall (E-W Firewall, red dashed line). The firewall sends the packets to the load balancer (Virtual Server Z, green dashed line), which forwards them to the real Server E (blue dashed line).

Traffic steering toward appliances can be achieved with a layer two or with a layer three approach, or a combination of the two. In a nutshell, in the layer-two method the E-W Firewall is configured to be the default gateway of Server C and a layer 2 network virtualization technique, such as VXLAN, is deployed to enable the two devices to communicate directly at the data-link layer through the Clos network where layer 3 Equal Cost Multipath (ECMP) routing is deployed. In the layer-three approach, a layer 3 network virtualization technique, such as Virtual Routing and Forwarding (VRF), is deployed to keep the traffic of subsets of hosts in the data center separate; the E-W Firewall participates to each of the subsets and propagates a default route in each one. Traffic steering in the data center Clos fabric will be the subject of a future post, but you can in the meantime find a detailed explanation in Section 2.7 of the book mentioned at the end of this post.

Independently of the technique used to implement it, service chaining causes traffic to be funneled into these discrete appliances, which in the data center network topology implies traversing several times the network fabric from leaf to leaf through a spine, a phenomenon commonly referred to as traffic “trombone” or “tromboning.”

This results in using up a multiple of the bandwidth required by each communication. For example, if we consider that East-West traffic accounts for about 90% of the overall data center traffic (or higher according to some analyses), in the previous example of server C talking with server E crossing two appliances, our sample fabric with an aggregated capacity of 153 Tbps will be able to carry only about 61 Tbps of host to host traffic. In other words, up to 92 Tbps of overall capacity are wasted due to traffic tromboning; and this amount grows when more appliances are chained or the percentage of East-West traffic grows.

Another disadvantage is that crossing multiple times the Clos network (three times in the example above), results in a tremendous increase in latency and jitter.

The root issue with the deployment of discrete appliances is that packet routing is determined by the placement of the appliances, not the source or destination host. Instead the whole point of deploying Clos topologies is to optimize and simplify routing, having only two hops between any two communicating endpoints, while leveraging ECMP routing to use all paths between the leaf and spine switches. With traffic tromboning through discrete appliances all the work done optimizing routing and resource utilization in the Clos network is gone!

The problems discussed above are only going to get worse for several reasons:

- The amount of bandwidth in the network is growing much faster than the capacity of the appliances;

- The amount of East-West traffic (traffic inside the data center) is exploding;

- More and more services are needed on the East-West traffic.

The solution

The only realistic way of addressing the growing challenges in providing services on East-West traffic is to implement such services, in a distributed fashion, at the edge, i.e., at the border between the network and the hosts. Services need to be applied before the packet enters a leaf switch, or immediately after it exits a leaf switch. Today’s edge speed is 25 Gbps for enterprise networks and 100 Gbps for cloud providers. State of the art technology enables services to achieve such capacity, especially when executing over domain-specific hardware.

Let’s consider where best domain-specific hardware and the corresponding services can be hosted at the edge. The data center edge is composed of three elements: the Network Interface Card (NIC) on the host, the wire between the NIC and a port of a leaf switch, and the port on the leaf switch. Conceptually domain-specific hardware can be hosted in any of these three elements: in the NIC, as a bump-in-the-wire, or in the switch.

Currently the best solution seems to be hosting the domain-specific hardware on a host PCIe slot. This requires such domain specific hardware to have a small enough footprint to be able to fit there and especially a power consumption not exceeding 25-30 W, which is the maximum value acceptable by many PCIe slots on commercial servers. It does not take away any valuable real estate, since that PCIe slot would have anyway been occupied by a regular NIC. This has also the added bonus advantage of providing services that by definition require PCIe access, such as offloads of RDMA (Remote Direct Memory Access) and storage (e.g., Non-Volatile Memory express over Fabric or NVMe-oF).

Placing services in a distributed fashion at the edge naturally leverages the same scale out model utilized for the compute. As the demand for processing grows, additional servers are added to the data center, hence increasing the overall amount of traffic to handle. However, this also increases the amount of PCIe mounted domain specific hardware available, and consequently the processing capacity dedicated to the distributed service execution and necessary to cope with the additional traffic.

While scale demands that services are implemented in a distributed way, their control and management must instead be centralized, otherwise the complexity of creating a distributed configuration is too high for the network administrator. When configuring a service the administrator should not worry about where that service will be offered. For example, when writing a security filter rule, the administrator should not have to know which element (i.e., PCIe mounted device) is going to enforce it (e.g., drop matching packets).

The most suitable model to achieve this is to have an intent-based configuration, e.g., in the form of policies, set up on a centralized controller that subsequently takes care of passing a corresponding configuration to the relevant execution engines that actually implement the service. Intent-based configuration means that an execution engine involved in implementing a policy can even be offline when the administrator defines the policy, but when it comes online its actual state is reconciled with the desired state. This approach is preferable over a transactional one that tries to update all the execution engines at the same time, as it could not succeed in many cases due to the very large number of PCIe cards participating in the distributed service execution.

Silvano’s book has a description of some of these topics in Section 2.7.

You can read an independent review of the book here.

The book was also listed in The Top 10 Best Cloud Storage Books You Need to Read in 2020.

Don’t Forget that Pearson/Addison-Wesley has a special offer on this book. To save 35% on the book or eBook go to the informit website and use code FUTUREPROOF during checkout to apply the discount. Offer expires December 31, 2020

Discussion and feedback